Your cart is currently empty!

This article would be much more useful if you explained precisely WHY a forward assist might be necessary. You didn’t,…

Updated

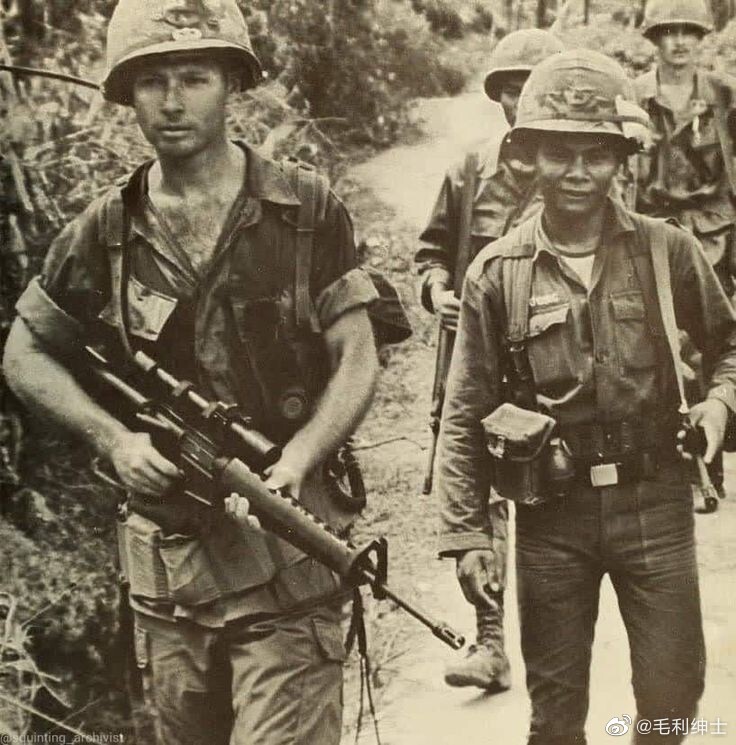

The M16A1 service rifle (Rifle, Caliber 5.56 mm, M16) is a lightweight, air-cooled, shoulder-fired weapon derived from the ArmaLite AR-15 rifle, intended for use by the U.S. military. It originally entered service in 1967 as an improvement over the M16 rifle, which was introduced in 1964 as the XM16E1. It was chambered in 5.56×45mm NATO and could fire with one shot per trigger pull or in fully automatic mode by means of a three-position selector lever.

The M16A1 instituted a few significant changes over the M16. The changes included a forward-assist, chrome-lined chamber and bore, and an improved flash hider. Most importantly, a regimen for weapon maintenance was developed that had been lacking at the time. However, the Black Rifle needed to overcome many hurdles to get to the top spot over 55 years ago. To understand the story of the M16A1, you have to go back to the end of World War 1, believe it or not. The U.S. Army Ordnance Department began conducting tests at Aberdeen Proving Ground in 1928.

The board recommended that all branches of service should transition to a smaller caliber round than the standard .30 caliber of the time. Combat lethality, weight of the individual cartridge, and a higher rate of fire with less recoil were all cited as reasons for the shift. A 6.8mm or .27 caliber was recommended and subsequently ignored as the Army wanted to stay with the “tried and true” .30 caliber. About 20 years later, after the Second World War, the U.S. military began looking for one sole automatic rifle to replace their current arsenal. However, there was no “One” answer. The M1 Garand proved disastrous in select fire, for example.

During the Korean Conflict, select-fire M2 carbines replaced the M1A1 Thompson and M3 Grease Gun. However, the .30 carbine round used by these weapons proved to be severely under-powered. The Ordnance Board again concluded that an intermediate-sized round was needed in the form of a small-caliber, high-velocity cartridge. They wanted it bigger than the pistol-inspired rounds such as .30 Carbine, but heavy–like the 45 ACP. Others asked for a round that was shorter and lighter than the .30-06 chambering of the M1 Garand.

Unfortunately, General Grade officers who were veterans of World War II and/or Korea still insisted on developing a powerful .30 caliber round. They wanted this round to see dual use in the development of rifle and belt-fed machine guns at the time. This led to the design of the 7.62×51 mm NATO cartridge.

The U.S. Army solicited different rifles for testing in order to replace the M1 in .30-06 Springfield. The Springfield Armory submitted the T44E4 and heavier T44E5. These were updated versions of the M1 Garand chambered in 7.62×51 mm NATO. Fabrique Nationale (FN) submitted the company’s FN FAL as the T48. A relatively new aerospace company called ArmaLite submitted several prototype rifles known as the AR-10 in late 1956.

Armalite’s AR-10 may have been the most radical of the group. These high-tech rifles had a very unique yet innovative design. They were built on aluminum alloy receivers, and were fitted with synthetic stocks and hand guards. The AR-10 had a rugged set of elevated sights and boasted an adjustable gas system.

The upper and lower receivers of the final prototype had a front hinge and rear take-down pin. The charging handle was mounted on the top of the upper receiver within the body of the carry handle, which also functioned as the rear sight’s tower.

Due to the use of aluminum receivers and plastic furniture, the AR-10 was an incredibly lightweight rifle, even when chambered in 7.62X51mm NATO. The AR-10 tipped the scale at a mere 6.85 lbs. The men who conducted testing found it to be the “best lightweight automatic rifle ever tested by Springfield Armory.” The Army ultimately chose the Springfield T44, a marginally retooled M1 Garand that accepted a 20-round detachable magazine over the Em-Bloc “clips” and had select fire capability. It entered service as the M14 and its first real look at combat was in the early days of the Vietnam Conflict.

Accounts from the front lines claimed the M14 was impossible to control in full-auto fire. Additionally, the weight of the ammo meant that troops were unable to carry sufficient combat loads to gain fire superiority. Especially when the enemy were armed with either SKS or AK-47 rifles that used shorter and lighter .30 caliber rounds (7.62X39). Although some troops were armed with M2 carbines with a lighter round and had a much more controllable and higher rate of fire, that gun was severely under-powered.

Big Army finally conceded that another rifle featuring an intermediate cartridge was needed. Something like what may have been proposed in 1928, for example.

The Army found itself reevaluating a 1957 request submitted by the U.S. Continental Army Command (CONARC). They wanted to design a select-fire rifle weighing chambered in the new round based on the .222 Remington Bench Rest cartridge.

Engineers at Remington lengthened the case of the .222 Remington by 2 mm. This aimed to produce ballistics closer to the longer and more potent .222 Remington Magnum.

The projectiles were intended to tumble when contacting a soft target like a human body instead of passing straight through like the .30 Carbine. Some of these supersonic projectiles fragmented and caused huge wound channels. These projectiles were so light that they allowed the rifle to be controllable in full auto fire with a cyclic rate of fire of 600 rounds per minute. The result was the .223 Remington (in civilian parlance) and the 5.56mm NATO designation given the round once it was adopted by the military.

This rifle was a smaller version of the Armalite AR-10 and used a similar gas system. It weighed 6 lbs. with a full 20-round magazine. The lighter weight of these rounds allowed the troops to carry more ammunition and have a higher sustained rate of fire in the field. It was dubbed the Armalite AR-15, and its inventor, Eugene Stoner, had unveiled it to the Army at a demonstration at Fort Benning, Georgia, in May of 1957.

The following year, the Army’s Combat Developments Experimentation Command ran war games by arming squads of soldiers with the issued M14 and the AR-15. This testing resulted in the command recommending the adoption of a lighter-weight, smaller-caliber rifle over the M14.

Once again, ignoring this test, the Powers That Be declared that all service rifles and machine guns had to use the same ammunition and ordered full production of the M14.

Despite that, advocates for the AR-15 courted Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay. After conducting similar testing to what the Army did, the U.S. Air Force adopted the AR-15 as its service rifle and ordered 8,500 rifles with 8.5 million rounds of ammunition. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) subsequently acquired 1,000 AR-15s and shipped them to be tested by the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN).

South Vietnam released extremely positive reports of the AR-15’s reliability in the field. The Vietnamese report revealed that the rifle suffered no broken parts after firing 80,000 rounds in one stage. Only two replacement parts were required for the evaluation of 1,000 weapons. The report came with the strongest recommendation that the United States should provide the AR-15 as the standard rifle of the ARVN. However, Admiral Harry Felt, Commander in Chief of Pacific Forces, rejected this after hearing the advice and counsel of the U.S. Army.

In 1962 and 1963, the military extensively tested the AR-15. The rifle was praised for its lightness and reliability. On the other hand, Army Materiel Command criticized its inaccuracy at long ranges and its lack of penetration at these ranges.

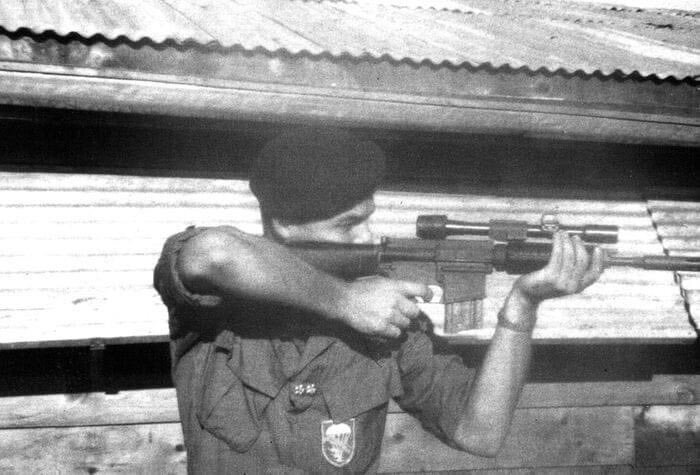

The U.S. Army’s Special Forces asked and were permitted to make the AR-15 their standard weapon. Requests from Army units such as the 101’st Airborne and clandestine units affiliated with the Central Intelligence Agency quickly followed.

At this time, Lieutenant Roy Boehm, who was developing the U.S. Navy SEALs at the time, was subjected to a Board of Inquiry over buying AR-15s over the counter instead of going through the Navy’s Bureau of Weapons. However, the investigation was closed after Boehm received authorization from President John F Kennedy after the president witnessed the rifle performing in a demonstration by the SEALs during a visit to their facility in Little Creek, Virginia.

More units began adopting the AR-15, prompting Army Secretary Cyrus Vance to investigate why the Army initially rejected it. It turned out that the Army Material Command rigged the earlier testing by using match-grade M14s while the AR-15s were standard off-the-shelf types.

By January 1963, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara determined and stated that the AR-15 was the best current choice as a weapon system and immediately ceased the M14 production and closed the Springfield Armory. The Department of Defense started mass procurement of AR-15 rifles for the Air Force, special Army units, and the Navy SEALs. The U.S. Army Ordnance Department had permission to modify the design as needed. The first modification was the addition of a forward-assist mechanism to allow a troop to force a round into the chamber if it failed to load properly.

Of course, the U.S. Air Force and the US Marine Corps objected to this addition, with the Air Force noting there was no record of malfunctions that the use of the forward assist could have corrected. Additionally, it was noted that the forward assist added weight and complexity to the manual of arms, which had the potential to reduce the AR-15’s reliability. The Air Force, Colt’s Manufacturing, and Stoner himself objected to it on multiple grounds, including the expense of retooling.

Colonel Harold Yount, who managed the Army procurement, later stated that the addition of the forward assist came as a directive by senior leadership and not from any test or complaint in the field. Yount testified: “The M-1, the M-14, and the carbine had always had something for the soldier to push on; maybe this would be a comforting feeling to [them] or something.”

After adding the forward assist and relocating the charging handle to the rear of the receiver instead of within the carry handle, the redesigned AR-15 was initially adopted as the XM16E1. The Air Force version lacked the forward assist and was adopted as the M16.

However, this rifle, already swirled in controversy, was about to have some teething problems in combat.

The small changes to the AR-15 did not include one feature critical to operating in a humid environment: A chrome-lined bore. Compounding this was a lack of an adequate cleaning kit for a smaller bored weapon than the .30 caliber weapons previously in inventory.

This led to a misconception due to advertising by the manufacturer, Colt’s Manufacturing. Colt boasted that the modern materials (aluminum and plastic) used in the rifle’s construction required little maintenance. This was somehow interpreted as the rifle being “self-cleaning.” Most cleaning used the wrong fluids, from water to mosquito repellent to aviation fuel, leading to further wear on the rifle.

Adding to this was an issue with ammunition. In 1964, DuPont announced that it could no longer produce the IMR 4475 rod powder according to the specifications provided by the Army. Competitor Olin Mathieson Company said its WC 846 high-performance ball powder could achieve the 3300 feet per second muzzle velocity. Yet this powder produced much more fouling, which induced stoppages in the rifle’s action when not properly maintained.

The most severe stoppage reported by troops was a failure to extract a spent case. There were documented accounts of dead troops holding disassembled M16s, which resulted in a Congressional investigation. Some troops claimed that the issued rifle contributed to more casualties than the enemy’s attacks.

Another, albeit less serious issue, was the rifle’s distinct three-prong flash hider that proved to be fragile and prone to becoming entangled in vegetation in a jungle environment.

Perhaps the most unique feature of the M16A1 service rifle is the ubiquitous carry handle. Yet one of the first things you were taught in the U.S. Military was to never carry the rifle by the handle. More importantly, it acts as a sight tower to hold the rear sight. This feature is largely absent on modern M16s and AR-15s and has been replaced by a Picatinny rail in most cases.

The carry handle was present on its predecessors to house the rear sight and protect the charging handle. On the M16A1, the rear sight is only adjustable for windage and can be adjusted by means of either a sight tool or a 5.56 NATO cartridge to hold down the detent and turn the wheel in whichever direction it is needed. Elevation adjustments are performed by raising or lowering the rifle’s front sight post.

For more accurate shooting, there is a groove in the top of the carry handle as well as a hole. This was intended for the ability to mount an optic, provided by Colt. The fixed power 3×20 telescopic sight included a bullet drop compensator, allowing the shooter to adjust between 100 and 500 yards. Other sights were available in later years, including the Trijicon ACOG and the ANPVS-4 night vision scope.

The rifle’s rear sight is a dual aperture flip-up sight shaped like the letter “L.” One is used for short-range out to 250 yards, and the other allows the shooter to range to 400 yards.

In order to eliminate issues with corrosion in the humid jungle environment of Vietnam and extraction of the spent cases, the bore and chamber of the M16 were lined with chrome. Additionally, a proper cleaning kit was issued with the rifle and a list of authorized cleaning agents and lubricants.

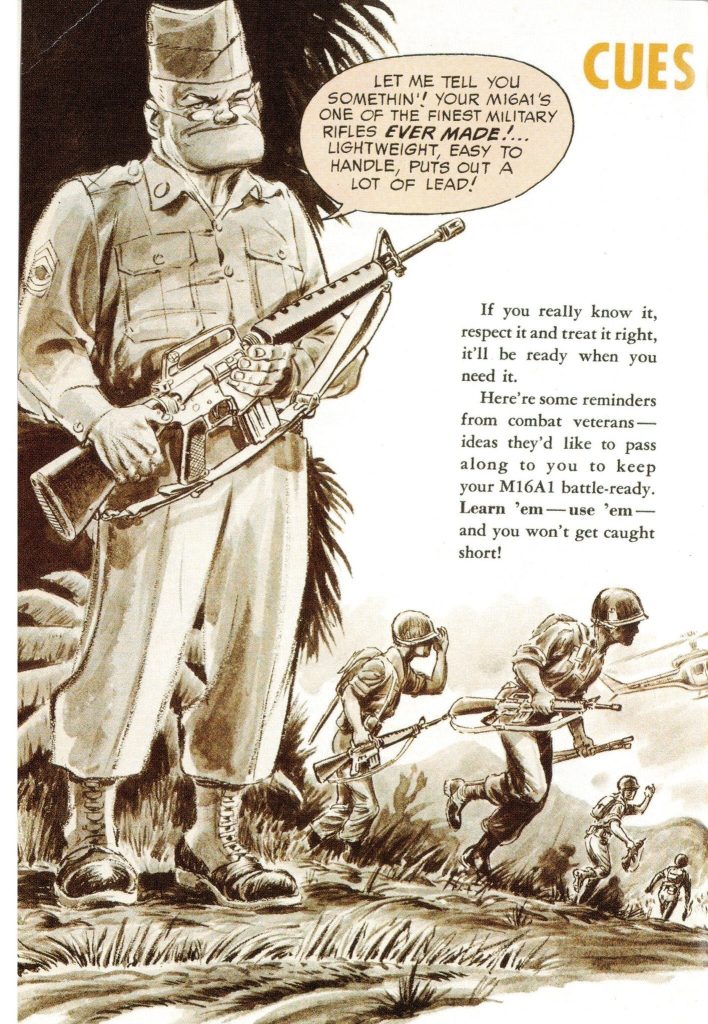

To its credit, the U.S. Military began intensive training programs for all troops. It went as far as to publish a cleaning and instruction manual in the form of a comic book, generously using illustrations in a storyboard format to educate the troops. Later versions of the rifle incorporated a compartment in the butt stock to store the cleaning kit. A raised section was incorporated around the magazine release, sometimes referred to as the “fence.” This was to prevent troops from accidentally hitting the magazine release while handling the rifle.

Lastly, the flash suppressor was replaced by a bird cage design that strengthened it, prevented it from catching on things, and decreased muzzle rise by acting in a sense like a compensator or a muzzle brake. These measures resolved issues with reliability, and the M16A1 emerged, leading to widespread acceptance by troops across all military branches. In 1969, the A1 officially replaced the M14 rifle as our nation’s standard service rifle, and in the following year, Olin introduced a cleaner burning propellant with its WC 844 powder.

Yet, the initial reports from troops in the field during the War’s early days continued to plague the entire M16/AR-15 platform. Although these issues largely disappeared with the introduction and adoption of the M16A1, the rumor mill continued to churn out misinformation about the rifle’s abilities that lasted into the 21st Century.

Despite these rumors, the M16A1 and its variants were manufactured by Colt, Harrington & Richardson, and GM’s Hydramatic Division until 1982.

Although superseded by the later M16A2 by the early 1990s, the M16A1 continued to see service by Reserve, National Guard Troops, and Law Enforcement Agencies well into the 2000s. For as many updates as the A2 and even later models received, a lot of troops preferred not only the simplicity of the M16A1 but the full auto mode over the restricted “3-round burst” mode and, of course, the smoother and crisper trigger of the A1 over the A2.

In many ways, it paralleled the idea of a classic car being phased out for more modern automobiles. It not only could be called the muscle car of the AR-15/M16 platform, it should be.

Or at least one of the muscle cars!

This article would be much more useful if you explained precisely WHY a forward assist might be necessary. You didn’t,…

Great article, deserving of a wide audience.

No, not just yet. As it turns out…having a set of molds made for injection molding is basically like finding…

We haven’t just yet. Turns out…having a set of molds made for injection molding is basically like finding out you…

Curry/Mike, I will always remember Terry’s stories about the shoot. Thanks for the memories. Kevin L.12/24

Leave a Reply